On February 18, 1965, students at Cambridge University assembled for a debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. on the topic of racism in America. Before a rapt audience, Baldwin spoke of not only the stolen labor of slaves that had enriched the Southern economy but also the daily humiliations of being Black — “the policeman, the taxi drivers, the waiters, the landlady, the landlord, the banks, the insurance companies, the millions of details 24 hours of every day which spell out to you that you are a worthless human being.” Buckley, in his famous mid-Atlantic sneer, responded that the economic condition of Black Americans had risen so greatly since slavery that they had, essentially, nothing to complain about. Of course, Buckley was lying through his teeth: Almost half of all Black Americans were living in poverty. His real disagreement with Baldwin lay at the social level. The odious behavior of a few individual whites was regrettable, but it was no great obstacle. The real problem was that Black people lacked the kind of serious moral and intellectual “energy” necessary to produce a professional elite. Instead, the civil-rights movement had encouraged a self-defeating posture of victimhood among Black people that young white liberals were all too eager to affirm. Thanks to the “generosity” of white Americans, Black people had already attained economic justice, Buckley suggested. The last thing they needed was social justice too.

Baldwin was declared the winner by a landslide. Sixty years later, the position of Black people in America has genuinely improved — a low bar — and contrary to Baldwin’s own predictions, America has seen its first Black president, a charismatic centrist who forcefully rejected the idea that “racial division is inherent to America.” But the question of so-called social justice — the idea that certain identity groups are wronged by the unequal distribution of social status — remains hotly contested today. That this idea has achieved a degree of cultural penetration is undeniable: When the right complains about “woke Hollywood,” it is not talking about nothing. But it is tricky to define social justice further without stuffing more straw into a straw man. Today the phrase is most often derogatory in tone; those who still speak unironically of social justice are generally publicists, consultants, and resistance grifters on Instagram. The mythic social-justice warrior — the woke, self-righteous, hypersensitive moralist who bathes in the blood of the canceled — is so caricatured at this point that one struggles to know how much of its imputed content is rooted in reality. What we can say is that the influence of social justice, whether real or perceived, was supercharged by the election of Donald Trump, a shameless if unideological racist whose authoritarian impulses made the idea of a societywide system of white supremacy increasingly plausible.

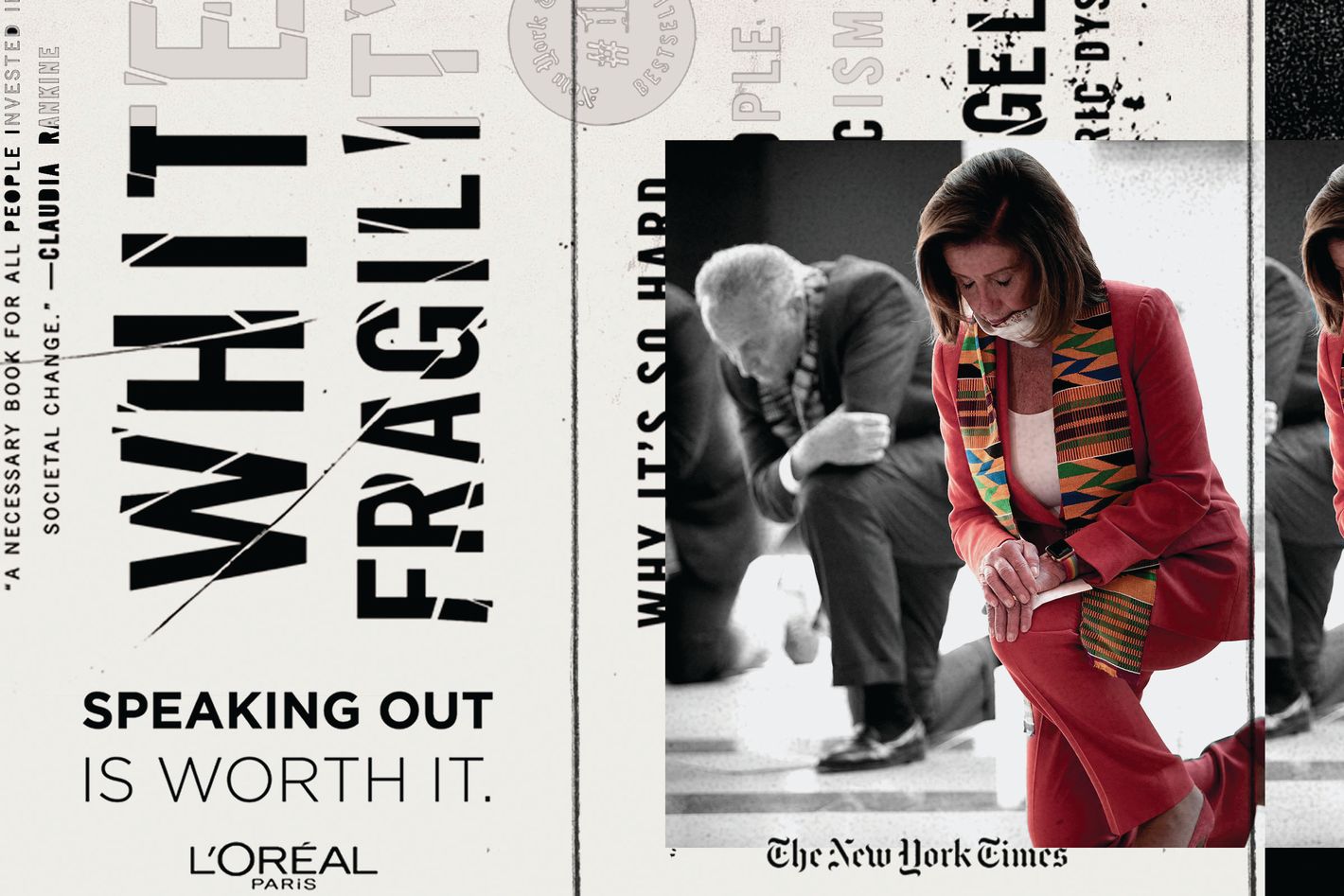

Perhaps no instance of social justice looms larger in the popular imagination than the summer of 2020, when the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police provoked protests and riots across the country at the height of the pandemic. The demonstrations, some of the largest in American history, recalled the long hot summer of 1967, when protesters whose lives had only been meagerly improved by recent civil-rights legislation ransacked storefronts in Newark and Detroit. Now photographs of a blazing liquor store in Minneapolis and club-wielding police officers in gas masks signified for some a renewed spirit of uprising and for others a lawless threat to democracy. (In fact, the vast majority of protests were nonviolent.) But the revolt was not a revolution, outside a short-lived autonomous zone in Seattle and some nominal budget reforms that fell short of defunding the police. What the nation got instead was a reorganization of the professional classes. Major corporations and cultural institutions took the opportunity to proclaim their commitment to social justice, installing new diversity-equity-and-inclusion programs. Anti-racist reading lists circulated online while prominent journalists and media figures lost their jobs over alleged micro-aggressions in the workplace. Congressional Democrats introduced their police-reform act by donning kente stoles and kneeling ridiculously in the Capitol. (What did not happen, we know now, was fewer killings by police.)

Critics of social justice sensed an opening. Later that summer, Harper’s magazine published an open letter warning that the ongoing unrest was weakening liberal norms of tolerance and free thinking in favor of “ideological conformity.” The letter, whose high-profile signatories ranged from Noam Chomsky to J. K. Rowling, ruffled all of the intended feathers, even if its successful brandishing of elite influence in the pages of a prestigious magazine deflated its own claims of chilled speech. The open letter was spearheaded by the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams, author of a memoir about “unlearning race” who liked to position himself as a centrist foil to Ta-Nehisi Coates, that bard of Black despair. Indeed, Williams was a Black dissenter in the mold of Albert Murray or Glenn Loury, the sort of anti-woke intellectual it would have been necessary to invent had he never managed to exist. (His first book, Losing My Cool, was about the deleterious effects of “hip-hop culture” on Black youth.) In the coming months, Williams would warn that a multiracial, college-educated social-justice movement had made George Floyd into a vessel for its endless litany of grievances. If Baldwin were alive today, he claimed, he would be forced to admit that the “criminal indifference” of white people 60 years ago (Baldwin’s phrase) has been replaced not by goodwill and human feeling but by the ruinous pursuit of an “ever more ineffable kind of social justice.”

Now Williams has written a book about the long hot summer of 2020. He has often imagined himself an heir of Baldwin; here, he could not sound more like Buckley. Summer of Our Discontent: The Age of Certainty and the Demise of Discourse offers a roughly chronological account of the past two decades, from the 2008 election to the protests for Gaza. But editorial indulgence has resulted in such a sludge of footnotes and block quotes that the eye must often dismount and continue on foot. The reader will find here no argument she could not have inferred from the titles of a dozen identical books on wokeness; nothing has been added but sentences.

Williams begins by claiming that there was a brief golden period when Americans might have joined together to avert the disaster of identity politics. This was the presidency of Barack Obama, whose election had promised a “postracial, genuinely progressive epoch of multiethnic social harmony.” But when the president stated that his son might have looked like Trayvon Martin, he betrayed in an instant the good faith of the American people. The nation had wished to give a Black man a chance to prove that he stood for all Americans. By identifying with a slain Black boy — by choosing, in effect, to be Black — Obama had made the “catastrophic” decision to “inject” race into a human tragedy. The nation, we are told, never recovered from this. I cannot exaggerate how literally Williams means this. “I am convinced a genuine opportunity was squandered,” he writes, explaining that Obama’s mistake opened the door for the vindictive tribalism of “social justice orthodoxy,” whose tactics of intolerance, intimidation, and violence were quickly “aped” by the far right. By the time of the George Floyd protests, this fringe ideology had blossomed into the dominant cultural force in America.

Today, Williams claims, liberalism’s most cherished institutions have been hijacked by a “powerful class of racial gurus, experts, thought leaders, indulgence sellers, and doomsayers” who promote identity as the “single most potent prism” for viewing all questions in society. He has in mind here the “highly lucrative” cottage industry for anti-racist handbooks like Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility or Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist. How else to explain the fact that Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey made a “no strings” donation of $10 million to Kendi’s short-lived Center for Antiracist Research at Boston University? Woke professionalism, Williams decides, requires helpless white-collar workers to participate in “coerced and ritualistic behavior” like putting their preferred pronouns in their email bios and deferring obsequiously to the most marginalized people in the room — or even outside it. “I was booked for a virtual lecture with a major Fortune 100 company in the Pacific Northwest,” Williams recalls, “when, before I was given the floor, a local land acknowledgment was solemnly recited even though I was speaking from Paris.”

It may interest Williams to know that the left is perfectly well aware of how large corporations and their designated intellectuals have co-opted social justice since the summer of 2020. Recent books like Olúfemi O. Táíwò’s Elite Capture and Jennifer C. Pan’s Selling Social Justice both offer compelling (if limited) accounts of this process, whose absurdity rarely taxes one’s skills of observation. (Pan quotes a June 2020 tweet from the official Twitter account of a popular fruit snack: “Gushers wouldn’t be Gushers without the Black community.”) But Williams assumes that the institutional uptake of progressive ideas — the ones that yielded DEI programs, greater diversity in Hollywood, and Pride collaborations with designer brands — represents a win for the progressive left and not, as it almost certainly is, a net loss. As Pan observes, the same companies that created DEI departments in 2020 have “simultaneously engaged in tax evasion, union busting, and relentless political lobbying to roll back labor protections.” Any good Marxist can tell you that the ruling class of any nation will frequently make social concessions as a way of buttressing its brute political power with moral credibility. What makes these concessions effective is that the sentiment behind them is often genuine: It really is objectively better not to be misgendered at work. But anyone who thinks that the brief ubiquity of corporate diversity trainings is proof that the radical left wields great power and influence in America has quite simply never sat through a corporate diversity training.

This is one legacy of 2020: the privatization of social justice. When writers like Williams speak of social justice today, they are referring almost exclusively to the management of large companies, elite schools, and nonprofits backed by the wealthy. And why? Because critics of social justice tend to inhabit the exact professional milieu where social justice has been most thoroughly integrated with the endless pursuit of profit. It does not occur to Williams to ask why a Fortune 100 company would solicit a lecture from Thomas Chatterton Williams, a Black public intellectual who, just like Kendi, tells people how to feel about race for a living. The social-justice warriors whom Williams most despises are not looters or rioters. They are people he encounters in the literary magazines he admires, at the conferences he is invited to, and among his students and colleagues at Bard College; many of them are Obama Democrats whom he once regarded as comrades in the post-racial project. Liberal intellectuals like Williams have thus experienced the rise of DEI less as a generalized threat to the democratic order and more as a personal betrayal by the institutions that they had, until recently, believed it was their job to defend. What they fear most is that liberals like them have been seduced by illiberal habits of thought. In other words, the greatest danger is not the barbarians at the gate; it’s the barbarians safely behind it.

How did things get so bad? Williams gives the same answer as Buckley: Things are bad because things are pretty good, actually. “Discontent has exploded even as life in the United States in real terms has never been better — or fairer — for black people and other historically disadvantaged minority communities,” claims Williams, citing the “seismic, indisputable victories” of the civil-rights movement. Racism is no longer the governing force in the lives of Black Americans, he argues; what remains are disorganized and isolated incidents, like lost Confederate soldiers who missed the news of Lee’s surrender. Yet certain vocal Black people continue, regrettably, to turn every Black man killed by the police into a symbol for a kind of white supremacy that, thanks to Dr. King, no longer exists. Here Williams quotes Alexis de Tocqueville, who argued that the closer a social group comes to achieving equality, the more zealously it tries to close the gap. “It is not always by going from bad to worse that a society falls into revolution,” wrote Tocqueville in 1856. “It happens most often that a people, which has supported without complaint, as if they were not felt, the most oppressive laws, violently throws them off as soon as their weight is lightened.” (This is sometimes called the Tocqueville effect.)

That, says Williams, is what made the summer of 2020 so long and hot: The general amelioration of racism in America had left many Black people with a festering need to “revolt against something.” In his famous case for reparations, Coates argued that “no statistic better illustrates the enduring legacy of our country’s shameful history of treating black people as sub-citizens, sub-Americans, and sub-humans than the wealth gap.” But this much-touted wealth gap, Williams tells us, largely reflects the disparity between the richest Black people and the richest white people, with reassuringly narrow gaps among the lower classes. Williams relies here on the arguments of Adolph Reed Jr. and Walter Benn Michaels, a pair of grouchy class-first Marxists who have long made the case that social justice is, at best, a program for “redistributing skin colors” more evenly within the upper classes rather than an attempt to redistribute wealth. It should be pointed out here that, unlike Reed or Michaels, Williams is clearly against the redistribution of wealth. (He was horrified when activists stated that, in a just world, the Poetry Foundation would give away its $257 million endowment to “those whose labor amassed those funds.”) Instead, Williams is content to observe that skin colors are already well distributed among the poor and whatever inequalities remain are certainly not worth burning down a liquor store over.

Let us assume that Williams is correct that Black people no longer face serious economic injustice in America. (He is not.) Is there anything else worth fighting for? It is important to remember that Coates was talking about more than the wealth gap. His point was that this economic injustice was evidence of a basically social injustice that (ironically, given the stated aims of the essay) could not be solved through wealth redistribution alone. “The essence of American racism is disrespect,” Coates writes, although he has often struggled to define it further without resorting to unhelpfully metaphysical language. But Williams is guilty of worse. “We are slaves, each of us, but only to our freedom,” he writes in Losing My Cool, reproaching his generation of Black kids for mimicking the degrading racial stereotypes they saw on BET. Of course, Williams would not deny that Black people still occasionally find themselves on the business end of an intolerant remark or suspicious glance; his own brother was violently assaulted by a police officer in his front yard. But Williams is an old-fashioned existentialist. He fell early into the canyon of Camus and has never rolled himself back out again. He has absolute faith in the power of individuals to transcend their historical circumstances. “Real dignity,” Williams writes in his second memoir, “can never be stripped from you because only you have the power to bestow it upon yourself.” One hears Buckley again, informing Baldwin that the people most suited to alleviating the humiliations of racism “are Negroes themselves.”

Thus Williams would have us believe that white supremacy today is a mirage cast across the moral desert by the Tocqueville effect; all it reflects is the jockeying of an increasingly multiracial elite. But Tocqueville, it turns out, had his own thoughts about racism. In his travels across antebellum America, he observed that racial prejudice was “stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where slavery still exists.” In Tocqueville’s estimation, this was because the Southern plantation owner had no need for bigotry: He had the lash and the legislature. In the North, by contrast, whites lacked a well-defined “barrier” between themselves and free Blacks. Hence, Tocqueville wrote in Democracy in America, “the prejudice that repels Negroes seems to grow as Negroes cease to be slaves, and inequality is engraved in mores in the same measure as it is effaced in the laws.” This is a very different story! Williams claims that a decrease in economic inequality has made Black people more resentful of those fewer privileges still denied them. But Tocqueville’s shrewder observation is that rising legal and economic equality indirectly produces social inequality as the dominant class is forced to confront the prospect of forfeiting its dominance. This is why prejudice seemed to increase in the Northern states. Both Blacks and whites, being formally equal, now perceived informal equality as a concrete possibility.

What Tocqueville suggests is that, in all eras of political change, the struggle for justice will inevitably spill out onto the terrain of civil society. The civil-rights movement, which Williams so pointedly admires, furnishes an excellent example of this. The movement could not have won legal rights for Black Americans if it had not first made those rights thinkable through a range of overlapping and conflicting tactics that included not just speeches and essays but also civil disobedience, armed patrols, and, yes, rioting and looting of the exact kind that Williams finds so loathsome today. In 1968, Hannah Arendt wrote in the New York Times that the widespread social unrest of the previous summer had amounted to an “unhappy substitute for organized power.” But in retrospect it cannot be denied that profound disruption at the level of civil society forced many white Americans to conceive of racism at all. It was, after all, civil society where Jim Crow exerted itself most brutally. Williams objects to the comparison of Trayvon Martin to Emmett Till on the basis that this elevates Martin’s death “from the specific to the eternal.” What exactly is “eternal” about Till’s murder, which for all its ghastliness was an entirely mundane affair in 1950s Mississippi, Williams declines to say. Lynching was, by design, a social institution among white Southerners, continuous with attending church or going to the picture show — not an act of state violence but the ultimate form of public judgment. “I do not call the citizens who executed the Negroes a mob,” a Texas prosecutor told the press in 1935. “I consider their action an expression of the will of the people.”

This is why the enemies of cancel culture cannot help but compare the firing of Hollywood directors to witch hunts. They implicitly understand canceling as a distinctly social harm, rather than a strictly economic or political one. After all, when Williams chides Obama for choosing to be Black; when he rebukes corporations for their woke HR initiatives; when he speaks balefully of sensitive college students — what could he possibly be asking for if not a more socially just world? For Williams, this would entail a “maximally tolerant society,” the kind where values of free expression and the open exchange of ideas are not only protected but “inculcated” in children by their parents. This is an amusing word choice for a man who hates orthodoxies of all kinds. But tolerance, he writes, works best when “buttressed by agreed-upon standards and a common investment in informal norms.” That is, Americans cannot have social justice until we first come to a consensus about what not to tolerate. (The Harper’s letter notably did not include any far-right signatories, for instance.) I cannot imagine any social-justice warrior disagreeing on this point. The question is who gets to contribute to this consensus — and who does not.

In the early weeks of the George Floyd protests, the Times published an “Opinion” piece by Senator Tom Cotton urging Trump to “send in the troops.” The essay provoked immediate backlash online, with some Times employees staging a virtual walkout and tweeting that the piece endangered Black people. Within days, the paper had issued a rare apology and secured the resignation of top “Opinion” editor James Bennet. For Williams, Bennet’s dismissal signaled a genuine “crisis of democracy,” a sign that the most respected paper in America had betrayed its commitment to free speech, “the bedrock for all subsequent rights and assurances” in a liberal society. Williams regards Bennet as the victim of a “multiethnic mob of junior employees,” some of whom were “not even journalists” but mere tech workers. Never in the paper’s history, he breathlessly claims, have its employees so brazenly dared to “mutiny their bosses.”

Now really, captain — mutiny? This is the language of a company man, not a freethinker. The worst injustice here appears to be the spectacle of privileged staffers openly defying the elite institution they were lucky to call their employer. (Williams was a contributing writer at The New York Times Magazine from 2017 to 2021.) The ousting of a single editor by his subordinates strikes Williams as far graver an affront to liberal democracy than the prospect of a would-be dictator unleashing the most powerful military in the world on American cities. Because the Times, he tells us, is one of the most important cultural institutions in the world; it cannot be handed over to the undeserving. “One immense side effect of social justice activism is the redistribution at scale of recognition and enrichment,” Williams writes, noting that Bennet had been a credible candidate for the newspaper’s top job. This is what the mutineers were really after: influence, prestige, and employment opportunities that they had not earned. The only difference between uppity Times staffers in Midtown and the roving bands of looters in Soho was that the law actually allowed looters to be roughed up by the police. Meanwhile, an “ascendant raider class” ran unimpeded through the Grey Lady’s hallowed halls, sacking the upper echelons and looting status itself.

So in claiming that something was stolen from Bennet, Williams effectively admits that Bennet had something worth stealing. It is all well and good to say that a janitor at the New York Times Building enjoys the same freedom of speech as the paper’s top editors do; but the fact is that the latter can use this freedom in ways the former could only dream of. This is why the Founding Fathers viewed free speech as inextricable from a free press, as indicated by James Madison’s first draft of the Bill of Rights. “The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments,” he wrote, “and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable.” Without the circulation of public opinion through the press, the founders agreed, democracy would be impossible. As Thomas Jefferson put it, “Were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter.” Of course, the speech of a newspaper does not emanate spontaneously from its soul; it takes capital, labor, and a means of distribution, and these are limited material goods that must be secured one way or another. (As secretary of State, Jefferson would fund a friendly newspaper by appointing its editor-in-chief to a lucrative sinecure in the State Department.)

There is, I think, a compelling case to be made that the American political tradition thinks of free speech not as the basis of a free press but as an instance of it. A newspaper is not a giant person; a person is more like a little newspaper. If this is so, then the vast majority of Americans have low budgets, limited circulation, and few dedicated readers, even in the age of social media. In other words, speech is a resource, not an inalienable property, and as such it is subject to the same regimes of theft, privatization, and accumulation that have swallowed up the labor of workers and the fruits of the earth. We have heard much lately about when free speech ends: the moment when protesting for Palestine becomes grounds for detention or deportation in the eyes of the police state, for instance. Less often asked, but equally important, is when speech begins. Did Cotton’s speech begin the moment that the Times published his op-ed? During the editorial process? When Bennet’s deputies pitched the idea? At what point, in other words, did the ordinary flow of money, labor, and influence through civil society stop? Well, never. To say that Cotton was too important not to publish is to say that he enjoyed a certain social position that deserved the paper’s famously discriminating attention. From the start, Cotton had more than free speech: He had actual speech, the very thing that protesters were being denied all across the country.

One of the principal goals of the protests of 2020 was therefore to seize the means of expression: protesters were not exercising their right to speak freely so much as they were trying to amass a form of social influence that could meaningfully compete at a national level. In other words, they were starting a newspaper; what Williams hates is that people started reading it. The fact is that telling a voiceless person they have free speech is like telling a poor person they have freedom of money: Nice work if you can get it! Williams might respond that a person who finds their ability to speak curtailed does not thereby lose their capacity to think. “Expression is the exterior form and, if I can express myself so, the body of thought, but it is not thought itself,” writes Tocqueville. It is seductive, I know, and highly flattering to those of us who write for a living, to suppose that thought “makes sport of all tyrannies,” as Tocqueville puts it. (At least the slave, Buckley had the gall to imply, had retained his freedom of thought under the whip.) But a thought without expression, like a soul without a body, is just as good as dead. Surely we cannot comfort ourselves with the idea that the brutal neck restraint that kept George Floyd from breathing nonetheless could not keep him from thinking. For in the end, we know it did.

The irony, of course, is that Williams’s book arrives at the very moment when the “gains” of social justice are already being dismantled: DEI initiatives will likely soon be a thing of the past, as will the whole Department of Education. Whatever cancel culture was, it did not involve literally sending the secret police to kidnap celebrities and ship them off to prison in El Salvador. The Supreme Court appears to be preparing to rubber-stamp, perhaps without explanation, some of the most extraordinary presidential powers in the nation’s history. But Williams will not allow looming fascism to distract him from the sacred work of punching left. He responded to Trump’s deployment of the military into Los Angeles during the anti-ICE riots by accusing protesters of re-creating the “calamitous visual language” of the Floyd protests, which he believes helped propel Trump to a second term. Who will he blame for a third? As for the basically puerile suggestion that we can only heal the Republic by cultivating good manners and open minds, we may refer again to Baldwin: “The sloppy and fatuous nature of American goodwill can never be relied upon to deal with hard problems.”

Meanwhile, the summer of 2020 lives on in unexpected ways. In the midst of the Floyd protests, an unknown 28-year-old democratic socialist named Zohran Mamdani was elected to the State Assembly seat that represents Astoria. His surprise nomination as the Democratic candidate for mayor of New York City has been explained by commentators across the political spectrum as a result of his embrace of concrete economic policies like free buses, rent freezes, and city-owned grocery stories. Mamdani’s sunny disposition, influencer-like mastery of shortform video, and preference for speaking in universal terms — housing as a human right, affordable food for all — have invited inevitable comparisons to one Barack Obama. Yet the liberal intellectuals who have spent the past decade bashing identity politics and the woke mind virus have not embraced him. Why ever not? The force of sheer xenophobia cannot be discounted: Mamdani is an ethnic Indian born in Uganda and a practicing Muslim. Then there is his promise to raise taxes on the rich, who turn out to be a formidable identity group when history requires it of them. But perhaps more than anything, Mamdani’s critics cite his stalwart solidarity with Palestinians in Gaza. They hate that he supports Palestine; but what they really hate is the idea that his support for Palestine helped him win.

There are good reasons to believe that this is true. As Lydia Polgreen has observed, Mamdani’s almost genial weathering of constant charges of antisemitism proved to many voters, especially younger ones, that the candidate had “core beliefs on which he was unwilling to compromise.” But it is not simply a question of Mamdani’s moral character; it is also a matter of a certain latent social potential. It is impossible to imagine that Mamdani’s razor-thin primary victory in 2020 did not owe something to the ongoing nationwide protests. (Astoria’s early voters began casting their votes the day after the massive Black Trans Lives March swept through Brooklyn.) In the same way, a direct line may be traced back from Mamdani’s recent primary victory to the protest encampments for Gaza at Columbia, which acted not only as ground zero for an international student movement but also, implicitly, as a critical test of what it meant to be a New Yorker. “There’s no place for acts of hate in this city,” Mayor Eric Adams told reporters after violently breaking up the encampments. But the sort of city where young students would risk facing off with the NYPD’s counterterrorism task force is precisely the sort of city where pie-in-the-sky ideas like free buses and city-owned grocery stores suddenly feel possible. The antagonists are, after all, identical: The billionaire hedge-fund manager Daniel Loeb, for instance, who is currently leading an effort to ensure Mamdani does not win in November, was part of a group of wealthy donors who urged Adams to sic the police on protesters last year.

Another way to put this is that all social movements are also intellectual movements: They both contribute to and rely on the ideological groundwater of society. Williams would have us believe that someone who smashes a storefront window in Minneapolis or pitches a tent in Morningside Heights is engaged in the opposite of thinking. But the panicking ruling class wasn’t just interested in flattening the encampments or quelling the looters; it wanted to crush the ideas that these things represented. This is what Baldwin was getting at when spoke of the “spiritual state” of America. “The political institutions of any nation,” he wrote in The Fire Next Time, “are always menaced and controlled by the spiritual state of that nation.” What he meant, I think, was that every time a person contests or defends a political situation, they are also contesting or defending the intellectual terms on which that contest is conducted. You cannot fight without fighting about how you fight. That is why Williams cares so desperately about what the summer of 2020 made us think, even if the protests manifestly failed to achieve their objective goals; it is also why liberal institutions were so eager to snatch up these ideas and exhaust their potential before tossing us back the husks. What Mamdani’s win suggests, however, is that they did not get them all.

More From Andrea Long Chu