It’s easy to romanticize the idea that you could make one massively successful indie game and then put your feet up while Steam sales keep the dollars trickling in – and that absolutely does happen – but a big hit doesn’t necessarily drive people to rockstar lifestyles or early retirement. You might be financially freed up to do whatever you want, but rather than bonding with the couch on a molecular level, “whatever you want” might just be making more games.

Stardew Valley creator Eric Barone said last year that his one big splurge after his farming sim lit the internet on fire was a proper PC that considerably improved on his old “hand-me-down” system. Jordan Morris, creator of the Metroidvania game Haiku, the Robot and the Stardew Valley-inspired idle farming sim Rusty’s Retirement, describes a fairly similar experience after Rusty sold around 550,000 copies.

I spoke to Morris about his game dev philosophy and how his success has impacted his life and ambitions. He says the Rusty rocket didn’t dramatically alter his lifestyle, and he still has the same €1,000 PC.

“We’ve literally done nothing else differently for the last year that Rusty’s been out,” he says of his family. “We just keep doing the same things that we used to do. The only thing that we’ve spent money on is getting this apartment, and that’s only because we felt like we’re starting a family, we need something bigger, and if we have the means then we should. And that’s it. But I still drive the same car. I actually still have the same computer. I mean, it wasn’t cheap, but it’s like a €1,000 computer from five or six years ago. It’s still doing good.”

Rusty’s Retirement enabled Morris to invest into Tokyo Game Show and Gamescom trips, but he says his goal “has always been to just earn enough to make more games,” and that comfort zone is where he’s staying. I asked how he balances games as an art and as a business, specifically with the types of games he wants to make versus the games that are likely to click with people. He says rapid prototyping is a key part of his process.

“I would say I have a list of ideas,” he explains. “All of these ideas seem good to me, things that I would like to make, and things that I would probably like to play as well. And this is what I did for Rusty, actually. Before Rusty, after Haiku, I had no idea what I wanted to make, so I had this list of ideas, and I would spend two weeks prototyping each idea. I just set a deadline of, I’m going to give myself two weeks to just make this into something so I can at least get a better idea of, is this idea good or not? And then after those two weeks, I would post it onto social media just to see what other people thought. And that’s how I landed on Rusty.

“I think it’s kind of a good way to balance it, because you have these ideas and you have these things that you want to make. So if you make a small prototype and then put it online, and then if that post gets traction, or people show a lot of interest in it, then I think that’s kind of a sign from the business side of, okay, there’s a demand for this. You’re kind of covering, ‘I want to make these things,’ but you’re also covering, ‘this specific one has low business potential.’ So yeah, I did that last time. I would assume I’ll do the same again, just because it worked out pretty well.”

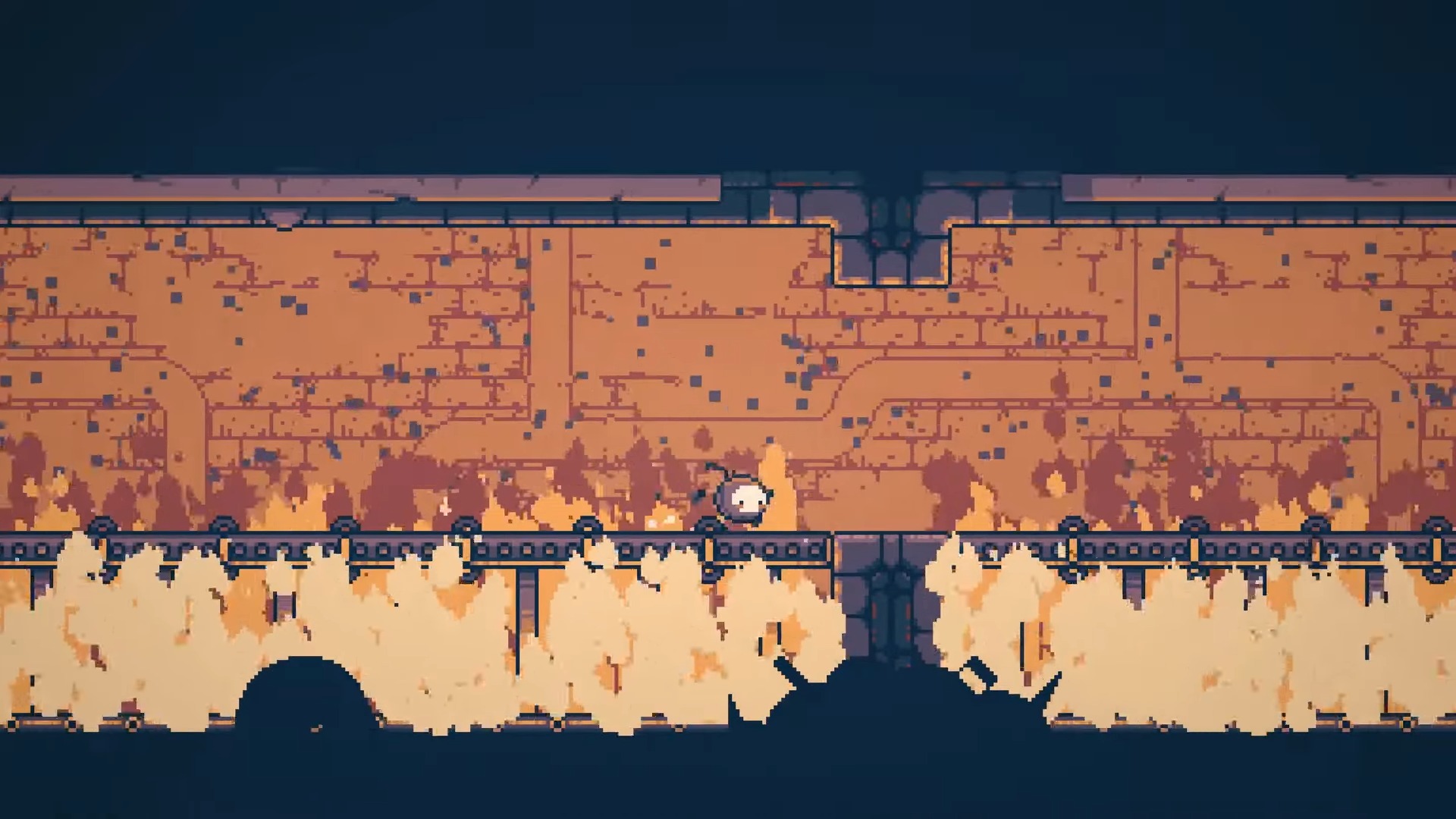

There’s some shared robot DNA between Haiku and Rusty, but otherwise Mister Morris games are hard to pin down. I asked Morris how he’d define his style, and he pointed to all the little things that add up during play.

“That’s a good question. I haven’t thought of that before. What defines a game made by me?” he ponders.

“I’d say cutesy, maybe. Robots obviously seem to be a theme here. And just a good time. As long as everything’s fun. I think I pay a lot of attention to detail, to the small things, the nuanced things. In a platformer, the controls need to feel great. I spent months and months on those controls, I remember. It’s like a house of cards in the back end. If I touch or change one thing, it’s all going to crumble down, but at least it feels good to play, which is what’s important at the end of the day. Just how it feels in the player’s hands. Even in Rusty, the progression and that sort of thing, I paid a lot of attention to make sure that it was well balanced and you could either play it casually, or you could play it as a min-maxer if you want to optimize it to the max.

“Making sure that there’s different ways to have fun, and making sure that it feels good,” he concludes. “Everything needs to feel good. I would say that’s one of my top priorities when I make a game. Does this action feel good? Is it understandable? Is it simple? Is it clear? But that’s a good question. I’ve never thought of that myself.”