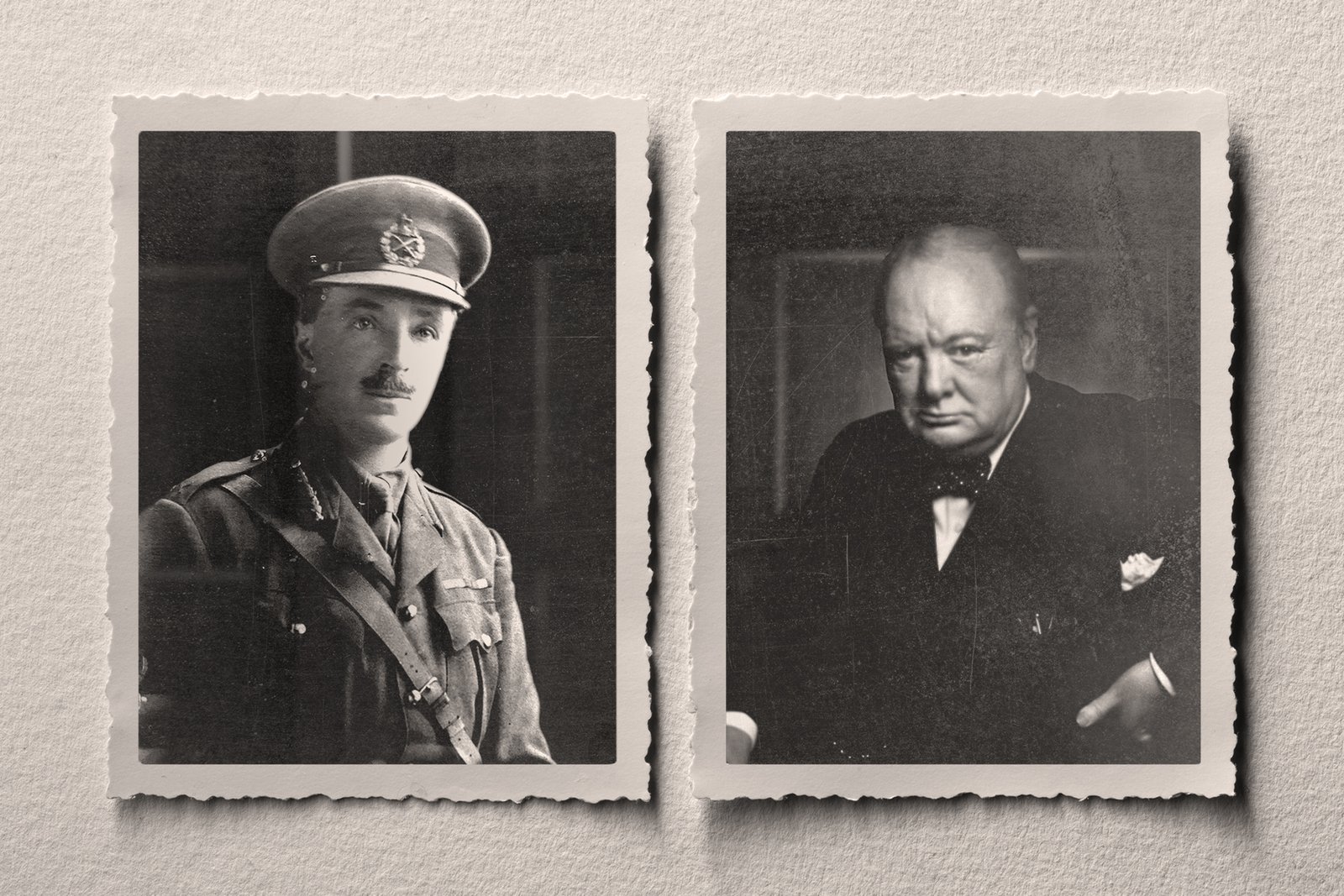

T he telegram on January 24, 1965, time-stamped 3:49 p.m., extended a formal invitation to an ailing, largely forgotten ninety-three-year-old British army general in Canada to attend the funeral of a famous ninety-year-old statesman in England: “Please cable if you can or cannot accept invitation to state funeral of Sir Winston Churchill St. Paul’s Cathedral London Saturday 30th January 1965 Stop.”

The invitation was delivered to a name and an address in a distant place, St. John’s, Newfoundland, the recipient presumably unfamiliar and irrelevant to the organizers of an event of global interest and historical significance. Major General Sir Hugh Tudor had lived a quiet life in self-imposed exile in Newfoundland for nearly forty years and, by 1965, was almost immobilized by the infirmities of old age.

He had not seen his old friend Churchill in twenty-seven years, but the friendship obviously remained as fresh then as when it began seven decades earlier. Their correspondence had continued until, it would seem, both lost interest in the diminished empire they had served and a society that, over time, had disappointed them.

Tudor’s name was on the list because he was prominent among the people who were still loved and admired by the great Englishman as he approached the end of his time on earth.

A broad outline of their lives offers a superficial explanation of the friendship between Churchill and Tudor. The two met frequently during the First World War, when Churchill served briefly as a battalion commander on the Western Front while Tudor was rising through the ranks as an artilleryman, soon to be the youngest divisional commander in the British army. Their contact at the front continued even after Churchill became a key minister in the wartime British cabinet.

By the end of the Great War, Tudor had been mentioned ten times in dispatches for gallantry in combat. He was promoted in the field to the rank of major general. At forty-seven, he was still young. His reputation was solid. His rank guaranteed a comfortable living and, at the end, a pension that promised a sustainable retirement. He had a young family—four children whom he hoped to help through all their youthful challenges and nurture to maturity.

Instead, within two years, Tudor was at war again, a brief war but one that consumed his hopeful future. In the spring of 1920, he was summoned by his oldest friend to serve the British Empire in another conflict, this one close to home—in Ireland. Churchill was, by then, British secretary of state for war.

In Ireland, as commander of the notorious paramilitary force the Black and Tans, Tudor waged a brutal campaign against rebel “terrorists,” one he was determined to win at all costs—including utilizing police death squads and inflicting brutal reprisals against members of the Irish Republican Army and supporters and Sinn Féin politicians.

Ireland was, in many ways, a hopeless war for both the British war minister and the British soldier on the ground. They both knew they had but one imperative—to win. Churchill found a way to define the outcome of the Irish war as a victory. But for Churchill’s friend the soldier, his engagement with the Irish War of Independence, in which his legacy included Bloody Sunday—November 21, 1920, when his men infamously slaughtered Irish football fans—marked the beginning of a long journey into personal oblivion, one that saw him leave his family and homeland in 1925 and move across the sea to Newfoundland, Canada.

W ednesday, November 25, 1925

The RMS Newfoundland was ten hours late as she slowly approached the narrow entrance to St. John’s Harbour just before one o’clock in the afternoon. Tudor, now in transition to civilian life, had survived nearly thirty-five years of active service in the British army: colonial skirmishes and intrigues in India, Egypt, and Palestine and in the Boer War; four years on the Western Front in the First World War; and, recently, a dirty war in Ireland.

But now the prospect of an open-ended stay in this grim seaport clinging to rocky hills was daunting—living in a settlement with centuries of history but little evidence of human creativity except for the overbearing churches high above the town. The situation had a bright side, though, as he would remind himself in the days ahead: he could expect no existential drama here. Newfoundland in 1925 was economically and politically unstable, but peace was not an issue in St. John’s.

The business Tudor had settled on was selling codfish—caught, salted, and exported from this rock in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, 2,300 miles away from London. As a cover story, the Newfoundland salt fish trade was a shrewd choice. Never mind that the general didn’t know a codfish from a halibut, the support of credible and well-established merchants in London and St. John’s would satisfy the doubtful.

Being inconspicuous was a large part of a carefully managed survival strategy. People who were intent on capturing or killing him wouldn’t recognize him out of uniform. And so it came to pass—Newfoundland became a refuge and, whether he had an inkling of it in 1925 or not, his life.

T he most intriguing of the Tudor mysteries in Newfoundland involves a failed attempt to kill him. As is the case with most mythology, it sounds plausible but there is little evidence to prove it.

Tudor wouldn’t have been hard to find. His move to Newfoundland had been reported in the British press, and from day one, he was conspicuous around St. John’s. For a potential assassin, it wouldn’t have been difficult to get to Newfoundland. Passenger liners from Liverpool, Halifax, and Boston arrived weekly. There were Irish citizens in Newfoundland, many of them priests who, unlike most Irish Newfoundlanders, had strong nationalist sympathies and bitter memories of the Black and Tans. They could have helped in a murder plot.

According to the most frequently repeated version of the story, two Irish gunmen arrived in St. John’s in the early 1950s and easily discovered where Tudor was living. One of the hitmen, both of whom were obviously Catholics, was said to have realized that, when the deed was done, he would be burdened by a mortal sin. He had a flash of fear about the future state of his immortal soul. It wasn’t likely that he’d have time for the sacrament of penance if he was on the run, so he decided to seek pre-emptive absolution. He confessed to an Irish priest, who, regardless of his politics, felt obliged to break the sacred seal of the confessional and passed the information on to the Catholic archbishop in St. John’s—who passed it on to the authorities.

In a less elaborate version, three men with Irish accents showed up on a priest’s doorstep one night inquiring where they might find “Hughie Tudor.” The priest notified the police, who picked them up and arranged for a speedy unofficial deportation. The weakness of that story is that there would have been no need for the Irishmen to have asked around for “Hughie.” Tudor’s name and address were in the St. John’s telephone directory for many years, and certainly in the 1950s.

All the versions of the assassination story suffer from the same flaw—the target was easy to locate and an easy mark for any competent assassin. But Carla Emerson Furlong, the last survivor among the people in St. John’s who were personally close to the general, firmly believed it. She didn’t hear about it from the general himself, though, and if the attempt had actually happened in the early 1950s, she was living in England at the time. But she knew that the IRA had murdered others in his Dublin circle, and to her it was entirely credible that he was in danger of assassination for as long as he was alive.

She had heard that the IRA was still hunting him long after he had come to Newfoundland, and from too many impeccable sources for it to be untrue. They would have had him, she believes, but for the fact that the archbishop found out “and sent them packing.”

Besides the lack of first-hand confirmation, the compelling yarn has other obvious weaknesses. The general was nearly eighty at the time of the alleged conspiracy. Most of his old adversaries from the Irish war were already dead or too busy with their lives and/or Irish political intrigues to embrace the risks, not to mention the expense, of committing murder in another country. And while it was simple to get to St. John’s as a tourist, leaving as a fugitive would have been more challenging. The likelihood of getting caught was high. The larger question would have been: Why bother? The passions that might still have been inflamed in 1925 would surely have dissipated by the 1950s. And yet the Tudor assassination plot is common currency in the history of Newfoundland, especially among clergy in St. John’s.

Larry Dohey of St. John’s, a devout Roman Catholic who was once, in his younger days, a candidate for the priesthood, heard the story in the 1970s from an older priest named Thomas Moakler. In conversations not long before he died in 2019, Dohey, who became a highly respected historian and archivist, was unprepared to say that he believed the story but was equally reluctant to dismiss it.

John Fitzgerald, a St. John’s historian, has made an exhaustive search of diocesan records for clues that could add credibility to the story. His search turned up one vague reference to a parish priest with Irish ties who was mildly reprimanded for his pro-republican pronouncements, but no evidence of any threat to Tudor. Asked if he believes the story, Fitzgerald shrugs. Like almost everyone who is familiar with it, absence of corroborating proof is insufficient to support a firm denial.

The Irish author Tim Pat Coogan visited St. John’s and included the assassination plot in a study of the Irish diaspora he published in 1999. While his account offers little new by way of proof, Coogan’s renown as a chronicler of the Irish independence struggle became a kind of imprimatur for those who find the plot to kill the general too delicious not to swallow.

A retired judge in Newfoundland, Gerald Barnable, has made an extensive study of Tudor’s time there and has heard many versions of the failed assassination story. Like any honest lawyer, he has an open mind about it. “The very frequent repetition improves plausibility,” he believes. “No one wants to give up this good story. The IRA wouldn’t deny it, showing as it does determination and long reach. What’s the harm? All ends well. No one is killed. What makes it unlikely? By 1950, you could kill Hugh Tudor with a rolled-up newspaper.”

Also, he argues, by 1950, “the IRA was not a force to be able to send men overseas.” The old warriors had more important things to occupy their time than tracking an old man in a distant, stormy place and raising the ire of yet another government—Newfoundland had become a province of Canada in 1949. From the IRA’s point of view, decades of exile on a foggy rock in the middle of the North Atlantic might have been punishment enough for anyone.

Adapted and excerpted from An Accidental Villain: A Soldier’s Tale of War, Deceit and Exile by Linden MacIntyre, published by Random House Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Copyright © Linden MacIntyre 2025. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.

The post The Mystery of the Assassination Attempt on Churchill’s War-Tainted Friend in Canada first appeared on The Walrus.