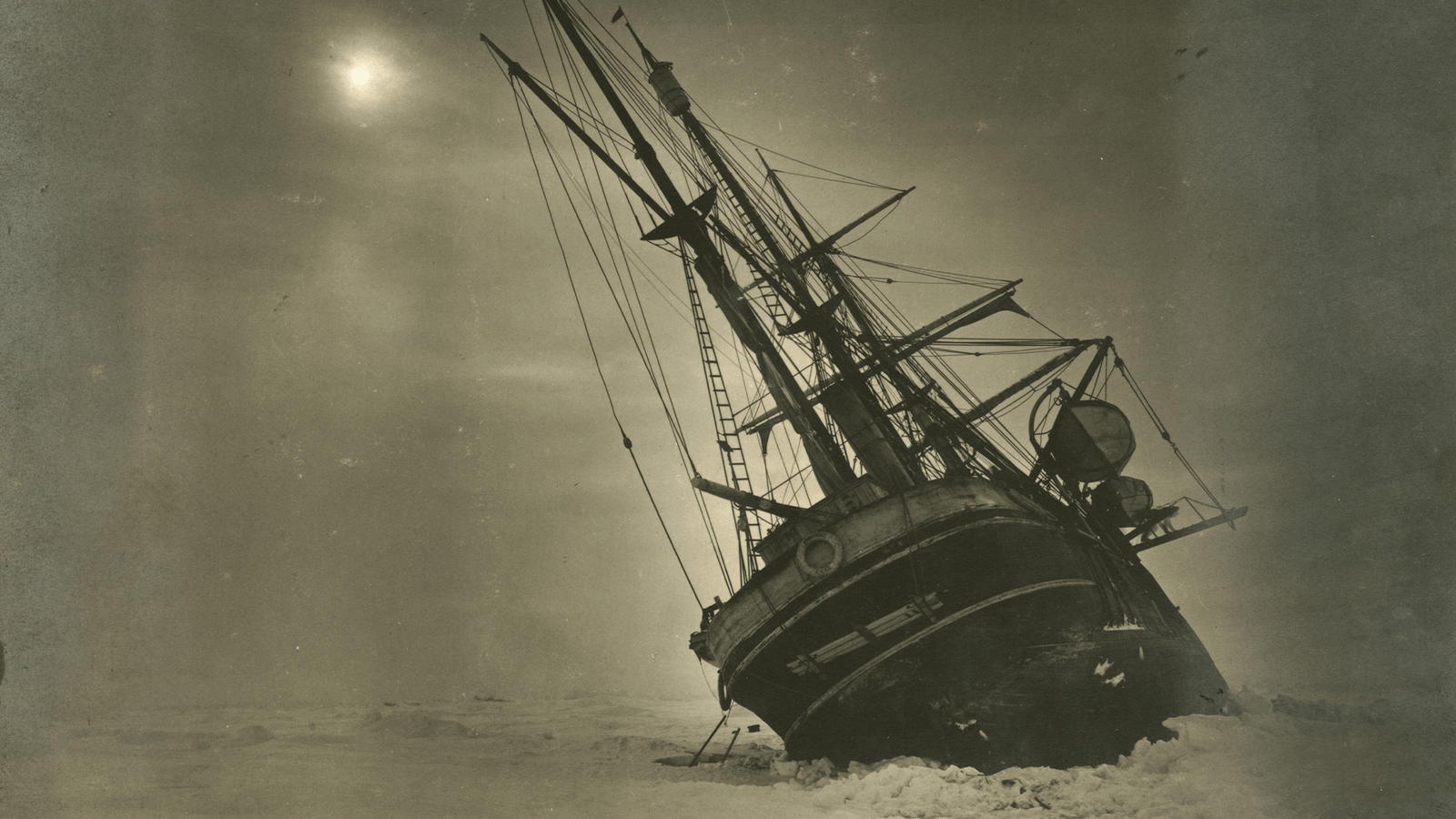

For almost 110 years, the Endurance has rested at the bottom of the icy waters of the Antarctic’s Weddell Sea. Long held as the poster ship for Antarctic exploration, Sir Ernest Shackleton’s ill-fated ship was no match for the crushing sea ice that sank it in November 1915. The legendary story of survival by its crew has endured ever since.

Widely considered to be the strongest polar ship of its time, Endurance was said to have one fatal flaw–a weakness in the rudder that caused it to sink. However, new research published today in the journal Polar Record shows that there were more structural issues onboard and that the famed explorer knew of these weaknesses. The new analysis from ice researcher and mechanical engineer Jukka Tuhkuri of Aalto University in Finland combines technical analysis with Shackleton’s diaries and correspondnece.

“Comparison with other early wooden polar ships is not favourable for Endurance,” Tuhkuri tells Popular Science. “It was not designed for compressive pack ice conditions as other ships of the time were.”

Tuhkuri was one of 15 scientists who joined the Endurance22 mission that uncovered the wreckage in 2022. The wreck’s discovery fueled his own interest in revealing the scientific truths behind the legendary ship.

According to Tuhkuri, simple structural analysis indicates that Endurance was not designed to handle the compressive pack ice conditions that eventually sank the ship. Compressive ice has been packed together by Earth’s gravity.

“The danger of moving ice and compressive loads–and how to design a ship for such conditions — was well understood before the ship sailed south,” Tuhkuri added. “So we really have to wonder why Shackleton chose a vessel that was not strengthened for compressive ice.”

Tukuri details Endurance’s structural deficiencies compared with other early Antarctic-exploring ships. The deck beams and frames were weaker than other ships. The machine compartment was also longer, which led to major weakening in a large part of the hull. Additionally, the ship’s hull also did not have any diagonal beams to strengthen it.

“Not only does this challenge the romantic narrative that it was the strongest polar ship of its time, but it also belies the simplistic idea that the rudder was the ship’s Achilles’ heel,” Tuhkuri said.

Tukuri also analyzed Shackleton’s diaries, personal correspondence, and other communications from the Endurance’s 27-person crew. He found that the reason that Shackleton chose to sail into the Antarctic ice pack is less clear than the ship’s structural deficiencies.

[ Related: Cracking open a 117-year-old Antarctic milk time capsule. ]

“Shackleton knew about this. Before he set off he lamented the ship’s weaknesses in a letter to his wife, saying he’d exchange Endurance for his previous ship any day,” said Tuhkuri. “In fact, he had recommended diagonal beams for another polar ship when visiting a Norwegian shipyard. That same ship got stuck in compression ice for months and survived it.”

Tukhkuri stresses that he is not here to judge Shackleton’s decisions or detract from the crew’s achievements. He only hopes that this adds more to how we look at Endurance over 100 years later.

“We can speculate about financial pressures or time constraints, but the truth is we may never know why Shackleton made the choices that he made,” Tukhkuri said. “At least now we have more concrete findings to flesh out the stories.”

While Endurance may be history, Antarctic sailing certainly is not. Tuhkuri is currently researching ice mechanics and arctic marine technology using the Aalto Ice and Wave Tank to find ways to keep ships safe as Earth’s poles continue to change.

“With global warming, sea ice [is] getting warmer (the properties of ice as a material are changing), but that may not decrease the forces from sea ice to ships,” he says. “That is something we are currently studying by conducting both laboratory studies in the Aalto Ice Tank, and field work both in the Arctic and the Antarctic.”

The post Ernest Shackleton knew ‘Endurance’ had shortcomings, new study says appeared first on Popular Science.