The call went out from WREC’s studios in downtown Memphis at 6:57 p.m. Central War Time: Doctors and nurses were urgently needed in communities south and west of the city. That was it. That was all the information the station was allowed to provide, despite the ongoing threat.

Three hours earlier, dark storm clouds over northern Mississippi had twisted themselves into a powerful funnel touching down near the town of Berclair and carving a path of destruction more than 110 miles long. By the time WREC issued its cryptic message, another eight tornadoes had ripped through neighborhoods, factories, forests, and farmland within a 100 miles of Memphis. The deadly storm would continue to ravage the central and southern United States from Illinois to Alabama until just after 9:30 p.m. on the night of March 16, 1942.

At 10:55 p.m., the United States Office of Censorship in Washington, D.C., gave the Tennessee radio station permission to inform the public about the tornado outbreak. For almost two years in the 1940s, the federal government exercised strict control over such weather reports, a World War II-era precaution that caused unexpected havoc on the home front, including on that dark March night in Tennessee.

Weather censoring begins

A few months prior, on the morning of December 18, 1941, the Upper Midwest had woken up to almost no weather at all. The United States was newly at war with Japan and Germany, and meteorological data was suddenly a military asset. The United States Weather Bureau field offices along the shores of Lake Michigan were some of the first to curtail their forecasts, no longer allowing the public access to barometric pressure readings, wind velocity and direction details, and observations of storm movements over the lake. In Muskegon, Michigan, the Weather Bureau predicted only that the day would be “fair and colder.” In Chicago, the iconic weather map at the Board of Trade went blank.

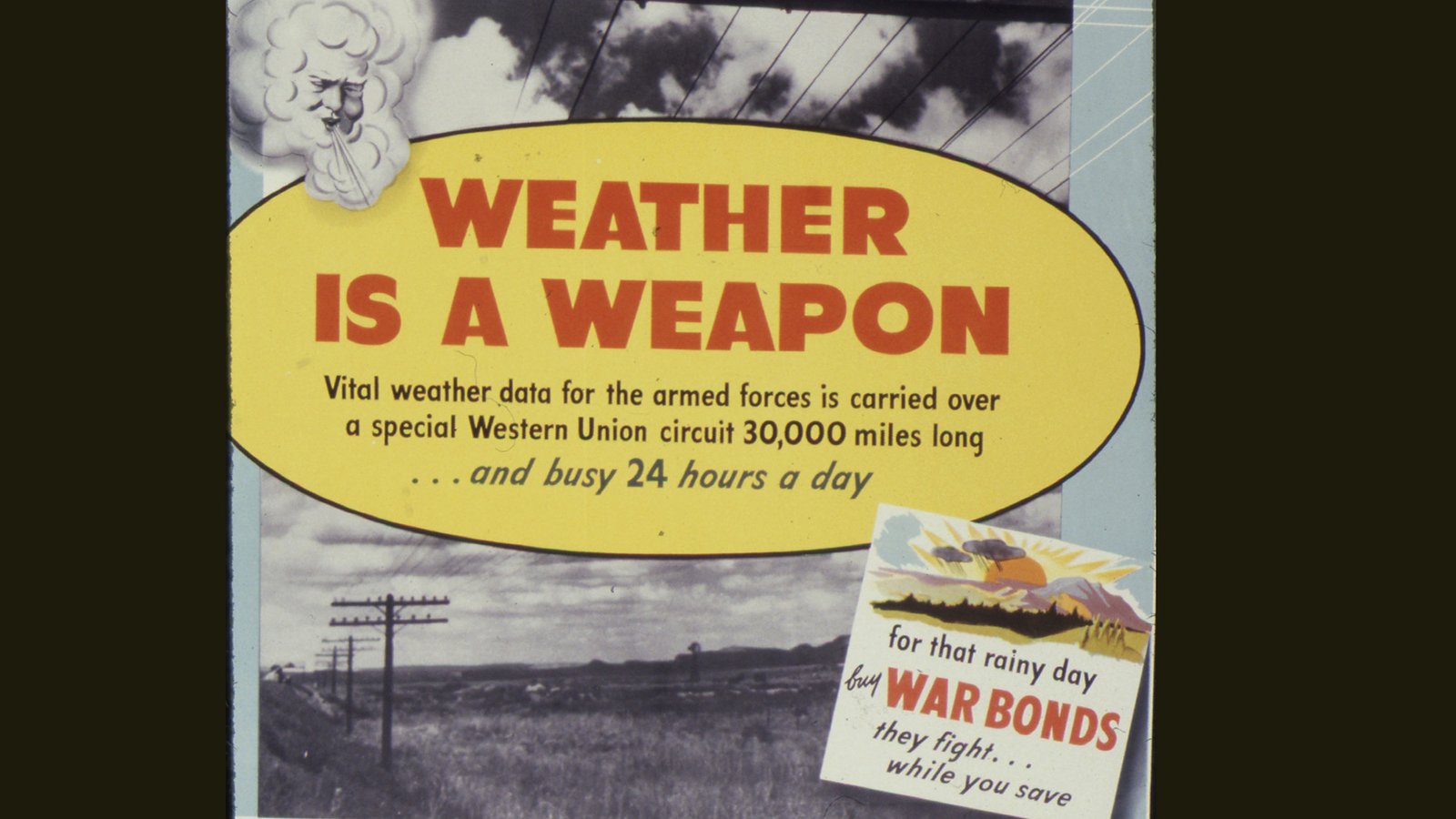

The availability of even these truncated weather forecasts would be further restricted less than a month later when the brand-new Office of Censorship rolled out its “Code of Wartime Practices” for American press and broadcasters. The codes—which were technically voluntary but diligently policed—limited newspapers to publishing official Weather Bureau forecasts and then only for areas within 150 miles of its base. Daily temperatures were released for not more than 20 cities at a time, and radio stations could broadcast information only when authorized. As clarified further in June guidelines, radio announcers were prohibited from airing “all weather data, either forecasts, summaries, recapitulations, or any details of weather conditions.” The West Coast was under even stricter U.S. Army guidelines, which required newspapers to wait 24 hours before describing the local weather.

“A few drops of rain at El Paso, high winds in Kansas City, and a snowfall in Detroit will indicate to enemy ships which parts of the coast will have rough weather or fog a day or two later,” the Office of Censorship warned in the nation’s newspapers.

The United States was not the only country to restrict weather reporting in World War II, but the idea seemed absurd to many, even in the patriotic “Loose Lips Sink Ships” culture of the early days of the war. “You can’t censor weather,” one Weather Bureau staffer scoffed to a syndicated-news reporter. “It keeps right on happening.”

And so it did, with consequences that ranged from amusing and inconvenient to expensive and devastating.

The costs of censoring the weather

A February cold snap surprised fruit farmers in northern Michigan, with layers of ice felling tree limbs and killing shrubbery. Meanwhile Florida’s Gold Coast publicly fretted that tourism would fall off without the newspapers’ daily reminders of its balmy temperatures in the midst of winter.

Across the country, doctors who had depended on accurate atmospheric pressure readings from the Weather Bureau to run certain tests were advised to acquire their own barometers. Baseball announcers were flummoxed over how to explain game delays. Even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt received a “stern letter” from the Office of Censorship for engaging in the most common of pastimes: complaining about the weather. “Between showers yesterday all of us had a little exercise and a little swim,” she wrote in her syndicated My Day column. “I woke this morning to a sky of clouds, which made me wonder if the sun would ever burn through.”

Losing trust in the Weather Bureau

Americans’ everyday lives had been built around the ability to predict the daily weather since the emergence of modern forecasting in the 1870s. The Weather Bureau—founded as part of the military in 1870, reconstituted as a civilian agency in 1891, and known today as the National Weather Service—had successfully established science-based forecasting as a “free public good,” says Jamie Pietruska, a historian at Rutgers University and author of Looking Forward: Prediction and Uncertainty in Modern America. “[The Weather Bureau] had to do a lot of work to sell the American public on the idea that it was possible for the U.S. federal government to produce accurate and reliable short-term forecasts because people already had almanacs,” Pietruska says, referencing the era’s popular compendiums of everyday facts and common folklore. “It wasn’t automatically apparent that short-term weather forecasting would be economically and socially valuable.”

But in 1942, the almanac had forecasts—the censorship office’s reach did not extend to such “weather indications”—and the radio didn’t. In that void, do-it-yourself prediction tools found their way into the pages of Popular Science and the unscientific “weather prophets” that the Weather Bureau had worked so hard to silence at the turn of the 20th century remerged, offering forecasts that relied on old wives’ tales or very gullible audiences.

The bureau tried to address some of these pressing forecasting needs. For instance, trusted agricultural firms could request government weather data directly, if they were willing to pay the cost of transmitting the information. Still, confidence in Weather Bureau forecasts tumbled. When a late-season hurricane threatened Miami, the U.S. government offered less than 24 hours’ notice of its approach, long after rumors of the storm had begun to swirl. “The weather bureau, when it was permitted at long last, gave out the truth about the storm,” the Miami News noted after the hurricane changed course, sparing the city. “But a great big percentage of the public had doubts.”

The 1943 Surprise Hurricane

The Texas gulf coast was not as lucky the following year. On July 27, 1943, a hurricane barreled into Galveston Bay, whipping Texas City with 104 mile-per-hour winds, dumping 17 inches of rain on La Porte, and killing 19 people on its path from Galveston to Houston. The region was accustomed to the violent storms that brewed in the Gulf of Mexico each summer, but no one had seen this one coming. Even the Weather Bureau had been taken by surprise. Forecasters along the southern coast were hampered by months of fear of U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico: the merchant ships that would have typically sent warning of the storms they encountered at sea were radio silent.

In the wake of yet another deadly storm, a Weather Bureau official promised that in the future all storms in the Gulf of Mexico would be publicized “from the time they are first detected,” but there was not much opportunity to test that pledge. At 12:01 a.m. Eastern War Time on October 12, 1943, the Office of Censorship lifted many of the restrictions on airing and publishing weather news nationwide. The war was far from over, but “the diminishing benefits from weather restrictions now appear to be over-balanced by the inevitable handicaps imposed on farming, aviation, shipping, and other essential activities,” director Byron Price said in an official government announcement.

Today, the Galveston Bay hurricane is remembered as “the mystery storm”—but there isn’t really much of a mystery: The residents of Texas’s most populous coastal area, like the residents of tornado-ravage Mississippi and Tennessee before them, were unprepared for the extreme weather because of the government’s decision to cut off access to weather information.

Other History Stories

The post During WWII, the U.S. government censored the weather appeared first on Popular Science.